Here in the NMSC archeology lab, we use our blog to highlight interesting and important artifacts we see in National Park Service archeology collections. Archeology informs our understanding of crucial and complex topics in America’s history. It teaches us how people worked and played, struggled and triumphed. As Valentine’s Day approaches, we know it’s been a rough couple of years. We could use some heartwarming history, and we think it’s time we used archeology to talk about how people LOVED! Here are a few artifacts we’ve seen over the years that illustrate the act of caring.

RINGS

Every kiss begins with… Boston National Historical Park? This pair of rings is from the archeology collection at BOST. They appear to be an engagement ring and wedding ring and are difficult to date precisely because of their simple design. Since ancient times, people have exchanged rings as symbols of love and commitment. Ancient Egyptians wore rings on the fourth finger of the left hand, believing that a nerve ran directly from that finger to the heart. Thousands of years later, that tradition persists.

The diamond engagement ring came to dominate the American market in the 1940s. Before that time, diamonds were just one stone among many that ornamented these rings. Married men did not typically wear wedding rings until the 1940s, but they have been customary for American women for hundreds of years. While researching for this post, I read about the gold double-band wedding ring that Alexander Hamilton gave to Elizabeth Schuyler upon their wedding in 1780. I read about the ring that Abraham Lincoln gave to Mary Todd, engraved with the words “A.L. to Mary, Nov. 4, 1842. Love is Eternal.” And I read about a wedding ring made from a red button, cut with a pocketknife and polished smooth, that Exeter Durham gave to his bride Tempie Herndon. Despite laws preventing their legal union, Exeter and Tempie wed when they were enslaved on the same plantation in the antebellum South. (Reyes 2021)

Now, we know that historically speaking, there’s a flipside to the romance of the ring. Traditionally, an engagement ring was not only a sign that a woman was “taken;” it also flaunted her fiancé’s financial status. In addition to symbolizing love and devotion, women’s wedding rings indicated men’s ownership of their wives. But it’s Valentine’s Day! And we’re feeling optimistic. Looking for somewhere to spend Valentine’s Day with your special someone? The National Park Service is full of beautiful scenery, fun activities, and meaningful places. It’s the perfect time to Find Your Park!

BABY BOTTLE

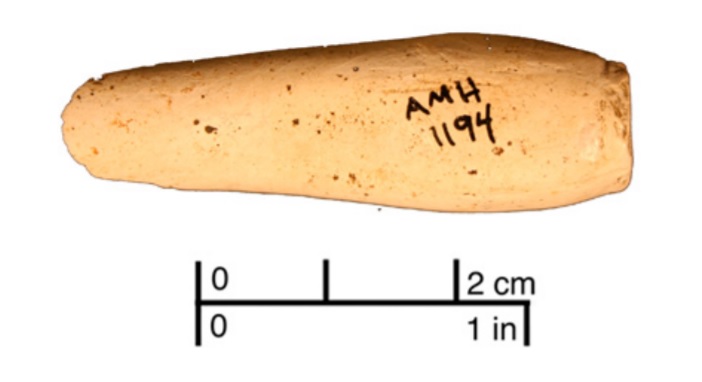

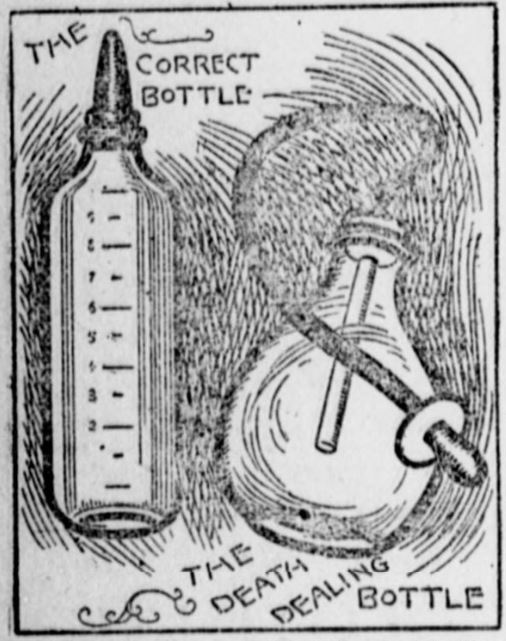

Strolling the baby care aisle or selecting a gift off a baby registry can be an overwhelming experience. The seemingly simple task of choosing a baby bottle can be dauting at best. Will a standard bottle do? Do you need a vented bottle or disposable liners? Are silicone or rubber nipples better for baby? Is your head spinning yet? People throughout history have sought the best ways to keep babies happy, healthy, and well fed. According to recent archeological discoveries, babies have been drinking from some form of bottle for 7,000 years! This 8-ounce glass baby bottle from the archeology collection at Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park is an example of the new and improved style of bottle that flooded the baby care market after the turn of the 20th century.

In the 19th century, many American babies were fed from pear-shaped bottles with rubber tubes and nipples attached. These bottles were later termed “murder bottles” because of their hard-to-clean design and tendency to breed dangerous bacteria. The dawn of the 20th century saw an emphasis on sterilizing baby bottles, and bottles like the one from FRSP were touted as easier to clean and safer for baby. One article that ran in several American papers in 1900 stressed the importance of using these new bottles, not the “old fashioned death-dealing horrors with a long rubber tube.” I can only imagine the distress of a well-intended caregiver upon learning that they had been feeding their beloved baby with a “death-dealing” bottle.

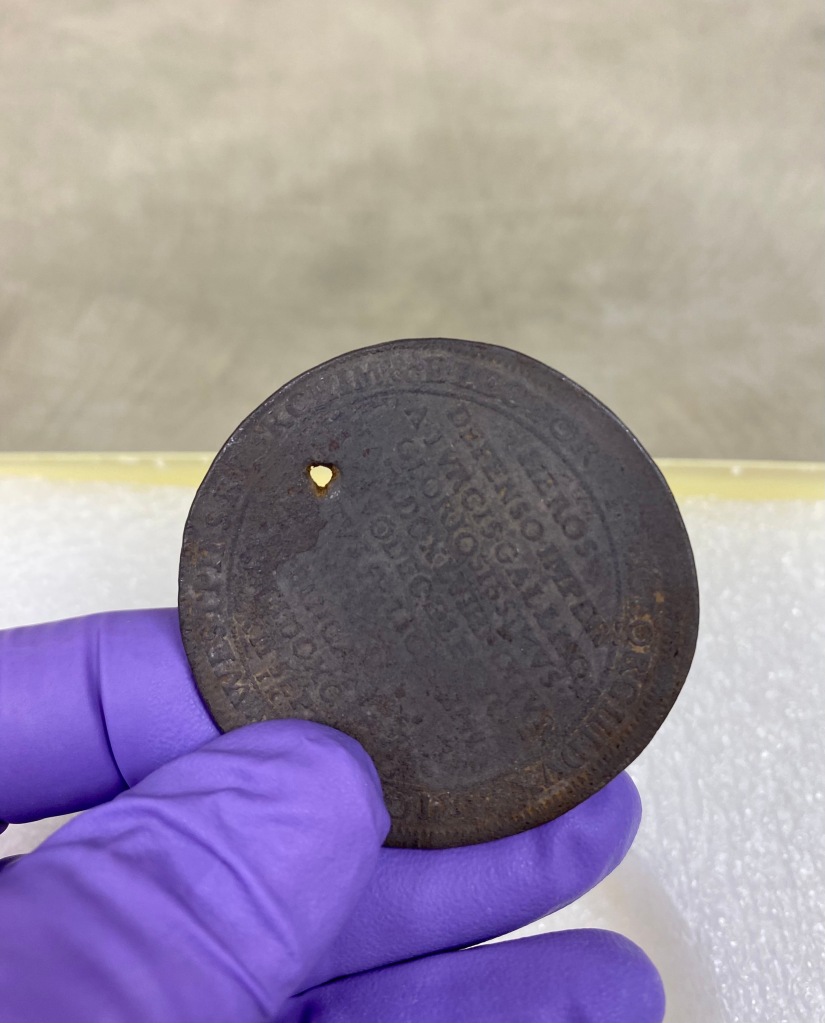

DAGUERREOTYPES

Before the advent of photography in the mid-19th century, possessing a portrait of a loved one required a good bit of money. With the invention of the daguerreotype in 1839, and the ambrotype and tintype a couple of decades later, people of middling and even modest means could afford to have their photograph taken. This meant that as soldiers left home to fight in the Civil War, many carried with them likenesses of their mothers, fathers, siblings, sweethearts, and children. Daguerreotypes, ambrotypes, and tintypes were small enough to fit in a soldier’s knapsack or even breast pocket. The size of these items can be seen to scale in this daguerreotype of an unknown woman from the collection at Historic New England. (See the cased daguerreotype in her hand?) This brass mat frame from the archeology collection at Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park probably once held a cherished likeness. It was recovered during a systematic excavation at the site of the 1863 Battle of Chancellorsville, and could have belonged to one of the 30,000 soldiers who were killed or wounded there.

Are you familiar with the story of Amos Humiston? If not, get your Kleenex ready. Humiston fought for the Union Army in the 154th New York Infantry. He was killed in battle in Gettysburg on July 1, 1863, and his body was discovered with this photograph of his three children in his hands. We can only wonder about the provenance of the empty frame from FRSP. Did this object bring strength or hope to an anxious soldier awaiting orders at encampment? Did it offer peace or solace to a wounded or dying soldier? We’ll never know. What we do know is that photographs in this era were overwhelmingly portraits treasured by family and friends. It’s likely that whoever owned this frame cared for the person whose likeness it contained.

MEDICINAL BOTTLES

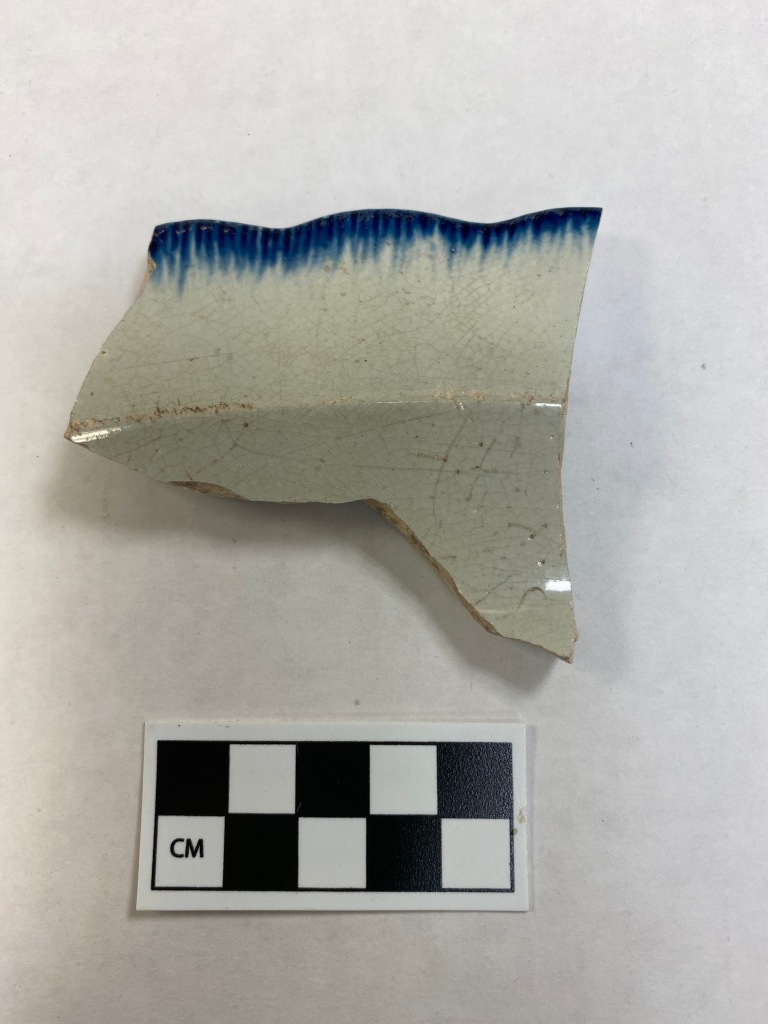

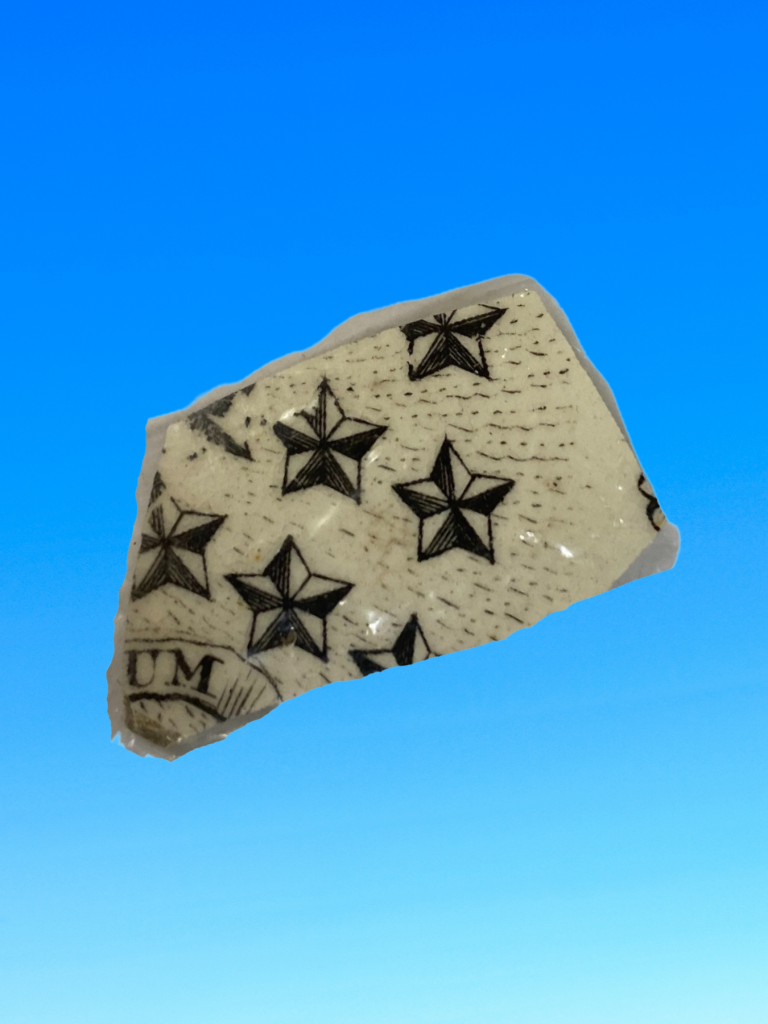

Archeological artifacts recovered at the Abiel Smith School in Boston suggest that teachers and staff may have provided not only lessons, but medicines as well, to their pupils. (Jordan 2021) The Smith School, located in what is now Boston’s Beacon Hill neighborhood, operated as a school for Black children in Boston from 1835 to 1855. Archeological excavations at the Smith School recovered a large number of medicinal bottles, including Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup, which was intended for use by children. We now know that morphine and alcohol, two main ingredients in the syrup, are not a good idea for little ones. At the time, however, this “medicine” was trusted as a cure-all and was dispensed to treat colds, colic, teething pain, and diarrhea (to name a few).

Mid-19th-century Boston was rife with disease, including yellow fever, cholera, and tuberculosis. The Black community was particularly vulnerable to these illnesses because of their crowded living spaces and their lack of access to health care. (Black people were barred from mainstream health care establishments and doctor’s offices, and the number of Black physicians in Boston fell far short of the need.) Children attending the Smith School found no better conditions there. With unhealthy conditions at home and school and nowhere to go for medical care, poor health was not uncommon among the Smith School student body. It’s hard to pay attention, to learn, to succeed, when you’re not feeling well. Bottles like this one may represent teachers’ efforts to improve students’ health, and therefore, their chance for an effective education. As stated by Dania Jordan in her thesis, More Than Just A School: Medicinal Practices at the Abiel Smith School, “administering medicine to the African American children and keeping them in good health not only fueled them with knowledge, but it allowed them the ability to overcome oppression, and combat racism.” (Jordan 2021)

Well, there you have it! These are just a few artifacts we’ve come across that represent the historical (and not so historical) phenomenon of caring. We’ll probably never see a centuries-old love letter come through our lab. (Paper’s pretty fragile, and usually doesn’t survive all that dirt). But if you look and listen, these artifacts have their own love stories to tell.

Artifacts contribute greatly to our understanding of history, but only when they are preserved in context. Please note that removing artifacts from National Park Service property without the proper permit is against the law. If you see an artifact on the ground, please leave it in place and tell a ranger. Thank you for helping to preserve our history!

REFERENCES

Please be advised that some of the websites used to research this post are not maintained by the National Park Service.

Byrd, Michael W., MD, MPH and Linda A. Clayton, MD and MPH. “Race, Medicine, and Health Care in the United States: A Historical Survey.” Journal of the National Medical Association 93(3) (SUPPL), March 2001.

“Civil War Photos: Help Sought to Solve Old Mystery.” Associated Press. June 11, 2012. Accessed via CBS news, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/civil-war-photos-help-sought-to-solve-old-mystery/

Climo, Lillian. “A Note from the Collections: Dangerous “Soothing Syrups:” Patent Medicines.” February 10, 2020. International Museum of Surgical Science. Accessed online at: https://imss.org/2020/02/10/a-note-from-the-collections-dangerous-soothing-syrups-patent-medicines/

Columbia University Digital Collections, https://dlc.library.columbia.edu/catalog/ldpd:113197

Franklin, Maria and Garrett Fesler, eds. “Historical Archaeology, Identity Formation, and the Interpretation of Ethnicity.” Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series – 0385. 1999.

Gallivan, Peter. “Unknown Stories of WNY: How a photo of his children helped identify a Portville soldier in Gettysburg.” WGRZ News, March 23, 2021. Accessed online at: https://www.wgrz.com/article/news/local/unknown-stories/unknown-stories-of-wny-how-a-photo-of-his-children-helped-identify-a-portville-soldier-in-gettysburg/71-dba141d0-b1cf-491d-9473-95e9988425a0

Gemological Institute of America. The Origin of Wedding Rings: Ancient Tradition of Marketing Invention? Accessed online at: https://4cs.gia.edu/en-us/blog/origin-of-wedding-rings/

Holden, Vanessa M. Slave and Free Black Marriage in the Nineteenth Century. Black Perspectives. African American Intellectual Society, 2018. Accessed online at: https://www.aaihs.org/slave-and-free-black-marriage-in-the-nineteenth-century/

Horton, James Oliver and Lois E. Horton. Black Bostonians: Family Life and Community Struggle in the Antebellum North. Holmes and Meier, 1979.

Howard, Vicki. “A Real Man’s Ring”: Gender and the Invention of Tradition. Journal of Social History. 36(4) 2003.

Jordan, Dania D. More Than Just A School: Medicinal Practices at the Abiel Smith School. Master’s Thesis, University of Massachusetts Boston, 2021.

Kansas Historical Society, “Unidentified Woman in Tintype.” Accessed online at: https://www.kshs.org/kansapedia/unidentified-woman-in-tintype/10262

Lockhart, Bill, Pete Schulz, Beau Schriever, Bill Lindsey, Carol Serr, and Bob Brown. Whitall Tatum – Part I – Whitall Tatum & Co. Society for Historical Archaeology. Accessed online at: https://sha.org/bottle/pdffiles/WhitallTatum1.pdf.

“Mary’s Wedding Ring.” Lincoln Home National Historic Site. https://www.nps.gov/liho/learn/historyculture/ring.htm

“Murder Bottles: Baby Feeding Bottles That Could Kill.” The Baby Bottle Museum. Accessed online at: https://www.babybottle-museum.co.uk/murder-bottles/

Oller, Mariana S. “…Upon the Subject of Wife.” The Alexander Hamilton Awareness Society, December 14, 2012. Accessed online at: http://the-aha-society.com/index.php/publications/articles/87-aha-society-articles/126-upon-the-subject-of-wife

Otnes, Cele and Linda M. Scott. “Something Old, Something New: Exploring the Interaction Between Ritual and Advertising.” Journal of Advertising 25(1), 1996.

Penner, Barbara. “A Vision of Love and Luxury”: The Commercialization of Nineteenth-Century American Weddings. Winterthur Portfolio 39(1), 2004.

Reyes, Angelita D., PhD. “Antebellum Plantation Weddings Among Enslaved Women and Men. Reconsidering Celebrations at Sites of Enslavement, Part 4.” October 18, 2021. National Trust for Historic Preservation. Accessed online at: https://savingplaces.org/stories/antebellum-plantation-weddings-among-enslaved-women-and-men#.Ygj7thso7IV

“Science Guards Baby’s Dinner: An Object Lesson to Young Mothers Regarding the Proper Care of the Nursing Bottle.” The Star. Reynoldsville, PA. October 24, 1900. Accessed via Library of Congress, Chronicling America. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/

“The History of Baby Bottles.” My Mom’s A Nerd. Accessed online at: https://mymomsanerd.com/history-of-baby-bottles/#:~:text=Baby%20bottles%20were%20invented%20as%20early%20as%20800%2D1200%20BC!&text=Researchers%20uncovered%20three%20ceramic%2C%20spouted,study%20in%20the%20journal%20Nature.

Vaugh, Emily. “Prehistoric Babies Drank Animal Milk From Bottles.” NPS, The Salt. September 25, 2019. Accessed online at: https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2019/09/25/764243209/prehistoric-babies-drank-animal-milk-from-a-bottle

Williams, Susan S. “The Inconstant Daguerreotype: The Narrative of Early Photograph.” Narrative 4(2), 1996.

Willis, Deborah and Barbara Krauthamer. Envisioning Emancipation: Black Americans and the End of Slavery. Temple University Press, 2012.

Wills House Virtual Identify: Philinda and Amos Humiston. 2021. Gettysburg National Military Park. https://www.nps.gov/gett/learn/historyculture/wills-house-virtual-identity-philinda-and-amos-humiston.htm

Yates, Juliet. “Put a Ring On It: Marriage and Symbolism in Pilgrimage.” Pilgrimages: A Journal of Dorothy Richardson Studies No. 9 (2017)